[Article as first printed in She Kicks Magazine, Issue 44, Nov 17]

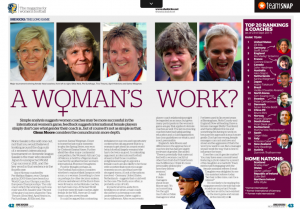

Simple analysis suggests female coaches may be more successful in the international women’s game, feedback suggests international female players simply don’t care what gender their coach is…but of course it’s not as simple as that.

Glenn Moore considers the conundrum in more depth.

Norio Sasaki is the odd one out, not that you would believe it looking around the dug-outs of a women’s international tournament or domestic league. Sasaki is the man who steered Japan to unexpected World Cup success in 2011, and the key word in that sentence is the fourth one.

Since Norway, coached by Per-Mathias Høgmo, won Olympic gold in 2000 there have been four World Cups, four Olympics and five European Championships. The only one in which the winning coach was male was 2011, Sasaki’s year. The rest of the glory has been shared by Tina Theune, Silvia Neid, April Heinrichs, Pia Sundhage, Jill Ellis and, this summer, Sarina Wiegman. Closer to home the last major domestic trophy, the Spring Series, was won by Chelsea’s Emma Hayes. Further afield the other major continental competition, the Women’s African Cup of Nations, is held by a Nigerian team coached by another former women’s international, Florence Omagbemi.

Food for thought, perhaps, as The Football Association considers whether to replace Mark Sampson with a man, or a woman. Something to chew on, perhaps, for other decision-makers, at home and abroad. At the Euro’s there were 16 teams, six had female coaches, ten had male ones. At the last World Cup there were 16 male coaches, eight female. In the WSL there are 13 male head coaches, seven female.

It could be argued this contrasting imbalance in success and opportunity confirms the old argument that for a woman to get ahead in a man’s world (which football largely remains) she has to be twice as good. A contrasting argument, in international football at least, is that those countries enlightened enough to appoint a female coach are also likely to be those with societies that most encourage women’s soccer, and thus have the strongest teams. A look at the nations involved – Germany, United States, Netherlands – suggests that could well be the case. The truth, as so often, is probably a mix of both.

In practical terms, aside from limitations on when a male coach should be in a dressing room with undressed players, there ought to be no difference. After recent events player-coach relationships might be regarded as an issue, but given many participants in the women’s game are gay that applies to female coaches as well. The key is ensuring coaches have had safeguarding education and a club/organisation has clear guidelines on what is, and is not, permissible.

England’s Jade Moore said differences in the approaches of coaches she has had are largely irrelevant of gender. She added: “There is potentially that maternal feel [with a woman coach] but other than that I don’t think there’s much difference. I think it’s more personality, philosophy – how they deliver sessions.”

Asked if male managers shout more Moore said: “It’s not something I’ve thought much about. Male managers is what I’ve been used to [in recent years at Birmingham, Notts County and England]. Now at Reading I have a female manager [Kelly Chambers] and that is different for me and something I’m having to work on because her approach is much more gentle. Don’t get me wrong, female managers can rant and rave and shout and be aggressive if that’s the word you want to use. But a manager should work the way that is best to influence the team.”

Does the coach’s gender matter? You may have seen a recent tweet featuring a photo taken by a parent of his daughter at a Garforth Town men’s match engaging with the female assistant referee. It read: “Daughter was delighted to see this assistant referee today, “her hair is like mine, can I be a referee?”

No one likely to be reading this magazine needs to be told that role models are important. Female coaches are all-but non-existent in the men’s game and remain in the minority in the women’s. That has an impact. I am a qualified Uefa B licence coach. This has meant working my way through the badges. Women are rarities in this milieu, usually one or two per course, and there are around 20 students on most courses.

In that respect nothing seems to have changed since former England coach Hope Powell was moving through the system. In an impassioned address to a 2015 FIFA conference she went through her progress to gaining the UEFA A licence, noting that every time she was the only woman, and only given respect by the men once she showed she could play (in my experience that, at least, has changed with male grassroots coaches far more accepting of women).

Powell also made the interesting point that, as the women’s game grows in stature, it becomes more attractive to male coaches, making it even harder for female ones to progress.

“More and more females are being squeezed out of the game from a coaching perspective,” said Powell, adding, “In the coaching domain there are opportunities for females to make a living in the game which is fantastic, but my concern is there are fewer and fewer coaching at the highest level. The FA, FIFA, UEFA, all talk about getting women qualified, let’s give them the opportunity to utilise those skills.”

The playing backgrounds of most men coaching in the women’s game is revealing. Put simply, they rarely made it to the professional ranks, let alone international football. This includes some of the most high-profile coaches: Sampson; Manchester City’s Nick Cushing; Canada’s Geordie coach John Herdman; the vastly experienced Watford manager Keith Boanas; former England caretaker and until recently FA Head of Women’s Elite Development, Brent Hills; Londoner Tony Readings who until recently coached New Zealand. The list is long. Former Wimbledon player Carlton Fairweather, Sunderland’s coach last year, was unusual in English women’s football in having a pro career.

One reason for this is that men’s football has a ‘show us your caps’ mentality. If you have not been a pro it is very hard to break into the game as a coach (of those who have, most worked their way up from non-League, like Lawrie McMenemy, while Roy Hodgson made his name overseas). Herdman was a youth coach at Sunderland where one of his charges was Jordan Henderson. However, he has since said he realised there was little chance that he, a former Northern League part-timer, would be allowed a chance at the top jobs. He moved to New Zealand working in coach education, then with the women’s teams. A similar calculation may well have been behind Sampson’s switch from working with male youth footballers at Swansea City, and adult non-League men at Taffs Well, to the females of Bristol Academy. He certainly rose quicker in the women’s game than he could ever have done in the men’s.

But what of the players. Do they care? Vivianne Miedema, who when asked was playing under a man (Pedro Martinez Losa) at Arsenal and won Euro 2017 under Weigman, said: “I really don’t care as long as it is a good coach and he or she knows how to handle the team. I don’t care if it is a man or woman.”

Current England players are mostly reluctant to comment ‘on the record’ on anything that might be construed as being either positive or negative towards Sampson, but the consensus appears to be they are more interested in a manager’s ability than gender.

One former England international, Becky Easton, told She Kicks: “I have played for a selection of both male and female coaches in my career at international and domestic level, and can honestly say that it doesn’t make any difference to me as a player. I believe the best coach for women’s football, probably all football, and even all sports, would be the one who has the greatest combination of coaching skills and people management skills, regardless of gender. In my experience, you often get one without the other.”

Ex-internationals Rachel Yankey and Pauline Cope concurred: “I don’t think it matters – the best person for the job,” said Yankey. “I don’t think gender should come into it. It should be who gets the best out of the team.” Cope added: “I don’t think it matters, but the way The FA work, they won’t want another man in charge now, that’s how I see it,”

That is probably true. Being neither English nor female Sampson was a departure for The FA and in the current climate it would be a surprise if they chose another man. North Carolina Courage’s Liverpudlian coach Paul Riley, a strong contender given his success in the US, said: “It is the dream job, but I think they want a woman coach, and there are a lot of good candidates like Mo [Marley, current England U17 coach and national team caretaker], Emma [Hayes] and Laura [Harvey, Seattle Reign].”

That trio are good candidates, but the field is otherwise quite thin. This is unsurprising. A Uefa A licence is required for the post. Of around 1,500 coaches with that qualification in England only 50 are female. In March the FA appointed Audrey Cooper as head of women’s coach development to lift that figure. She has a two-pronged approach. One is to work with newly created university-based women’s high performance centres and charter standard clubs to increase the base by encouraging women into coaching, from students to touchline mums. Secondly the 170 female Regional Talent Centre coaches are to be given bespoke training to upgrade their qualifications and learning.

That trio are good candidates, but the field is otherwise quite thin. This is unsurprising. A Uefa A licence is required for the post. Of around 1,500 coaches with that qualification in England only 50 are female. In March the FA appointed Audrey Cooper as head of women’s coach development to lift that figure. She has a two-pronged approach. One is to work with newly created university-based women’s high performance centres and charter standard clubs to increase the base by encouraging women into coaching, from students to touchline mums. Secondly the 170 female Regional Talent Centre coaches are to be given bespoke training to upgrade their qualifications and learning.

Other agencies are also getting involved, such as a new partnership between Women in Football and a gambling company that will put 50 coaches through their B licences. There are also programmes at grassroots levels. The Surrey FA has created a female coaches club. Emma Barnes, senior football development officer, explained: “We used to keep a database of female coaches and send them info and job opportunities ad hoc. We decided to make it more official. We had a really good response and have 70 coaches involved.”

Barnes aims to provide four field trips a season. So far they have been to Fulham’s training ground, to network and watch a session by the county coach, and Chelsea where the coaches watched the RTC in operations and, said Barnes, received “an inspiring address” from Hayes. Surrey have also put on all-female level 1 courses, and seek to add women to level 2 sessions in clusters, rather than in isolation.

Creating more coaches is, said Wiegman, imperative. While a believer in the best coach for the job, regardless of gender, she would like to see more women given opportunities in elite positions which means “we should educate more women so there are more female coaches to do the jobs.”

Opportunity is key, said Mark Parsons, another Englishman working in the US, at NWSL champions Portland Thorns. He said: “There should be more women coaches. They need opportunity. We have [former German No.1] Nadine Angerer as our goalkeeping coach, and have female assistant coaches. When a player like [Portland’s Canadian legend] Christie Sinclair retires we need to keep that expertise in the game.”

When it comes to England Parsons, who has ruled himself out of the job, said: “It should not be a woman, just because she is a woman, it has to be the best coach.”

Hope Powell disagrees. She said in October: “If you’d have asked me this question 20 years ago I’d have said ‘best person’ but now I think it’s really important that there are women role models and that people have someone to aspire to. I think that’s really important.” Newly retired Kelly Smith, now coaching at Arsenal, agreed. “I’d like to see a female take over.”

But they have to apply. In 2015 Scottish club Dundee United made headlines when they began a women’s team and received 50 applications for manager – all of them from men. The job required a B licence – but men are known to be much more likely to apply for jobs they are not fully qualified for. Sampson himself did not meet The FA requirements, lacking international experience, so having met him they re-wrote the job spec to suit. “We women – I generalise here,” said Wiegman, “should take chances and not be humble, sometimes we are too humble.”

The onus is on The FA to create more opportunities, but then on women to seize them, as Wiegman, Ellis, Hayes, etc have done. Nothing would provide a bigger boost to female coaching in England than a woman manager lifting the 2019 World Cup.