The team photo is such a part of football’s furniture that you rarely pay attention. We all have a few gathering dust. But look again at those taken before England’s last two World Cup semi-finals, the men at Russia 2018, the women at France 2019, writes GLENN MOORE.

NB.This article first appeared in #SK62 August 2020.

The England 11 ready to take on Croatia in the men’s World Cup SF in Russia, 2018. (PA Images)

The England 11 ready to take on Croatia in the men’s World Cup SF in Russia, 2018. (PA Images)

The men’s team featured five black players: Kyle Walker, Ashley Young, Dele Alli, Raheem Sterling and Jesse Lingard. The women’s team had two: Nikita Parris and Demi Stokes.

In itself that means little, but widen the picture. Each squad had 23 players. Gareth Southgate’s squad included 11 black players, Phil Neville’s squad…just Parris and Stokes.

Moving on, the last men’s squad, for the European Championship qualifiers of November 2019 had 14 black players, including seven who were not in the World Cup 23. The last women’s squad, for the SheBelieves Cup in March 2020…just Parris and Stokes.

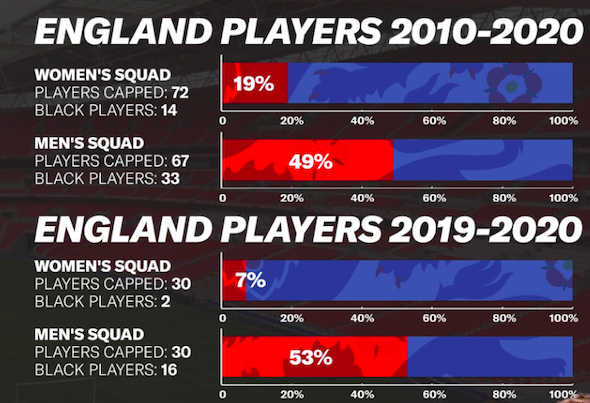

A blip? A phase? No. In the decade 2010-2020 there have been 67 men’s international players, 33 of them have been black (49%). In that time, 72 women have been capped, 14 were black (19%).

Every picture tells a story, it is said, but in the wake of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, it is time to ask what the story is behind these pictures.

The first witness is Hope Powell. Before becoming England’s first black manager, Powell won 66 caps playing alongside other pioneers such as Brenda Sempare, Mary Phillip and later Rachel Yankey. While they blazed a trail, it has been thinly followed since.

Powell, now manager at Brighton & Hove Albion, makes the point that the England team reflects the WSL in which “a very small percentage of players are black, therefore, this would translate to the national team selection.”

But why does the WSL lack the diversity of the men’s Premier League? Powell says: “Women’s football became a middle-class sport and less accessible for inner city/urban kids who cannot get to RTCs [Regional Talent Centres] because of affordability. In order to fulfil licence requirement, some centres have moved out of urban areas into the suburbs; kids of lower-income families can’t afford to access them, and therefore, fall out of the elite pathway opportunities.”

This view is shared by Anita Asante, winner of 70 caps. “When I began playing, the clubs all had centres of excellence and they were accessible, in cities; Arsenal were at Islington and Hackney. That cast a wide demographic net. Transport was easier; kids did not need to have parents who were able to drive them to venues. Some could travel independently, others go with adults on public transport. Now many training grounds are in rural areas. They are more challenging to get to. I look back and wonder whether I would have been able to get where I got to.”

Asante, who joined Aston Villa this summer from Chelsea, adds the issue is ‘complex’. She points to a less-developed scouting structure in the women’s game, the decline of school sport and a lack of visible role models and black facilitators. “When I got to Arsenal, the player taking the session and encouraging me was Rachel Yankey. I thought ‘this is a direction I want to go in’. It is not just players, but coaches, physios, every role in a club; those people who can say to a player in their community, ‘I’m involved in a club, come along.’”

ENGLAND’S BLACK SENIOR WOMEN FOOTBALLERS IN NUMBERS

BLACK PLAYERS CAPPED 2010-2020

Eni Aluko (2004-17, 102 caps)

Anita Asante (2004-18, 70)

Danielle Carter (2015-17, 5)

Jess Carter (2017, 1)

Jess Clarke (2009-2015, 52)

Gabrielle George (2018, 1)

Nikita Parris (2016-20, 50)

Lianne Sanderson (2006-15, 50)

Alex Scott (2004-17, 140)

Drew Spence (2015, 1)

Demi Stokes (2014-2020, 58)

Chioma Ubogagu (2018-19, 3)

Fern Whelan (2011-12, 11)

Rachel Yankey (1997-2013, 129)

Accessibility is only part of the issue. Powell and Asante both highlighted the historical problem of girls dropping out of sport at around 14-16. This is backed up by Keith Boanas, the former Charlton Athletic, Millwall Lionesses and Watford coach who has helped develop players such as Eni Aluko and Rinsola Babajide.

Boanas now coaches young players at Crystal Palace, a club which does use generally urban locations. He says: “We have a lot of black girls, the racial mix is about 50-50, but there is not the desire to take it on for most of them. I tried to get a 16-plus academy going but there is a lack of engagement and ambition. The parents are okay, they like the girls being active and involved in something like this; there are lot of unhealthy distractions in inner-city life they don’t want their children mixed up in. Women playing football is less frowned upon now; it is the girls themselves.

“It has always been an issue keeping girls in their teenage years, and if you lose them from the game, you lose them for good. In women’s football, you don’t get late developers like Jamie Vardy, Chris Smalling or Ian Wright. There isn’t the same non-league set-up and clubs don’t look for players in what there is.”

Boanas thinks greater visibility for successful role models such as Aluko, Alex Scott and Lianne Sanderson, all of whom are forging careers away from playing, will help. But Asante makes the point that Aluko’s ordeal in 2016-17, when after three Football Association enquiries, it was confirmed then-England manager Mark Sampson made comments to her that were ‘discriminatory on the grounds of race’, could be a barrier. “For young black women in Britain looking at elite women’s football, there are few representative figures,” says Asante. “Then they may look at what Eni encountered, someone they respect going through a very public conflict, and ask themselves ‘is that something I want to get into?’”

The FA did not come out of that controversy well, but they are making moves to address the women’s game’s lack of diversity. The first step was recognising the problem, and the diagnosis matches that of Powell and Asante.

Kay Cossington is Head of Women’s Technical at the FA. She has been at the FA 15 years, twice involved in restructuring the youth set-up besides coaching age-group teams, and also worked at Millwall and West Ham.

She admits: “Inclusivity was compromised as we attempted to turn more professional. We had 52 centres of excellence; that was too many for the depth of talent at the time. We reduced the centres to 30 to concentrate the talent, have the best playing the best; we’d seen from other nations that was fundamental to player development. But in solving one problem we created another: fewer centres meant they were less accessible.

“It could take two-to-three hours to get to one; that was challenging for families. Some also had a son in an academy, where the family made a decision to support the boy, not the girl. A lot of our players were good at other sports. They had to make a choice and we lost some.

“As the game became more professional, clubs moved to better training grounds; these were often further out. Millwall, who had trained in the heart of Lewisham and Southwark, two very deprived areas, moved to Bromley to provide better facilities. But the kids from the estates who used to walk to training suddenly could not get there. They were hotbeds of talent – that’s where players like Hope Powell and Katie Chapman came from – and we were missing them.

“The FA looked at numerous clubs and found this was a common theme. Players were increasingly drawn from the suburbs, not the inner cities, there were fewer BAME kids. In the men’s game there is the finance to move families, to put kids into schools, to provide financial help, but that isn’t present in the women’s game.

“It is not just finance; sometimes parents have to look after other siblings, or are at work. In trying to professionalise the game we were quickly becoming a middle-class sport.”

ENGLAND PLAYERS 2010-2020

England women 2010-20: Players capped: 72. Black players: 14 (19%)

England men 2010-20: Players capped: 67. Black players: 33 (49%)

ENGLAND WORLD CUP SQUADS 2018 & 2019

2018 men’s World Cup. England squad: 11 black players (48%).

Most recent squad (Nov 2019):*14/27 (52%)

2019 Women’s World Cup. England squad: two black players (9%) [Parris, Stokes].

Most recent squad (SheBelieves Cup, March 2020):*2/24 (8%)

*Includes players selected who pulled put through injury, and their replacements

ENGLAND TEAMS 2019-20

England women 2019-20: Players capped: 30. Black players: two (7%)

England men 2019-20: Players capped: 30. Black players: 16 (53%)

THREE of England’s cap centurions are black: Scott, Yankey, Aluko.

It was not, she adds, that black girls necessarily stopped playing, but they disappeared from view. Cossington recalls: “During the times when there were very few members of FA staff on women’s football full-time – myself Hope, Rachel Pavlou and Brent Hills – we did not have the resources to talent ID across all aspects of the game, so all players for England age-group teams were drawn from the centres of excellence.”

As funding grew, the net was cast wider. Initially, rural areas, where the women’s football structure was underdeveloped, were targeted. In the South West, The FA found the talent was playing boys’ football and discovered England Under-18 striker Katie Robinson. Newly signed by Brighton from Bristol City, Robinson is from Newquay and, says Cossington, “would never have been found under the old model.”

Following the success of another pilot scheme, in the East region, the strategy went national with the new Lioness Talent Pathway. This has an increased focus on urban areas in partnership with the EFL Trust. Ten inner-city EFL clubs are in a programme educating community coaches on identifying talented players and referring them on. “Some players with potential may need [emotional or financial] support, so we help with that,” adds Cossington.

If a black player does make it to international level, The FA’s BAME coach mentee programme has supported black coaches with opportunities to work within the national age-group teams, providing the players with someone they may better relate to (as Asante did with Yankey).

All this will take time. As recent age-group teams illustrate, the racial imbalance between boys’ and girls’ teams will continue in the near future. But, Cossington, echoing Gareth Southgate, stresses: “We want to see a diverse national team that represents how our country looks.” She adds: “Ultimately, we want to win medals, but at the same time, have a diverse game.”

These goals are symbiotic, for England are currently missing out on talent. Black players may have been few in number, but some have made a big impact. Three of England’s cap centurions are black: Scott, Yankey and Aluko. Another seven players – Asante, Sanderson, Powell, Phillip, Parris, Stokes and Jess Clarke – have reached the 50-cap mark. Parris was the second Women’s Footballer of the Year and plays for European champions Lyon

Parris came from Toxteth, Scott from east London, Clarke grew up on an estate in Leeds, catching the bus to training on her own at 15 as her single mum was at work. There are plenty more Parrises, Scotts and Clarkes out there. The FA hope they will no longer go undiscovered.

REMEMBERING THE PIONEERS (All of the following gained 50 or more England caps, unless stated):

Mary Phillip (DEF): Went to 1995 & 2007 WWCs, Euro 2005 and captained England in 2006 (in place of Faye White).

Hope Powell (MID): Player between 1983-1998 (went to 1995 WWC) and manager 1998-2013.

Brenda Sempare (MID): Played at 1984 unofficial World Cup and 1995 WWC.

Samantha Britton (MID): Went to 1995 WWC and Euro 2001.

Una Nwajei (FOR): 3 caps (2002-03) and went on to star in Norwegian Toppserien.